- Home

- Yarbrough, Shannon

Are You Sitting Down? Page 3

Are You Sitting Down? Read online

Page 3

“Thank you,” a polite voice yelled back.

These were the extremely proverbial sounds of my daily trek to the grocery for midday snacks of gizzards or tater logs. My bulging belly pushed up against the table was proof enough of my loyalty. I had always made the occasional stop for a weekend snack for me and Helen and a tank of gas. It wasn’t until Justin passed away that stopping here became more frequent. At first, coming here was just an escape from Helen’s monotonous crying. Long after the crying stopped, Helen spent her time either sleeping most of the day or bitching at me when I was around. Coming here cured the latter.

Seeing Travis outside was like a hard smack across the face, like that old gag in black and white movies where someone steps on a loose board on the floor and it flies up and pops them in the nose. Looking at me, he winced like someone does when they see someone in pain in a hospital. I had not seen that look of sorrow since Justin’s funeral. I don’t blame him. I wrinkled my nose at the sight of myself in a mirror. There are no mirrors in our old house that I even fit into. Luckily, I had no hair to comb. I held my teeth in my hand to brush them. The facial hair gene had skipped me growing up so I didn’t have to shave. It’d been years since I’d seen my own face, about two years to be exact. The look in Travis’s eyes told me I hadn’t missed out on anything.

Travis still looked as charming and supple as the day Justin had first introduced him to us. Helen had never cared much for the boy, shunning him for taking Justin away from her. She selfishly knew Justin deserved a better life than here with us, but she had preferred Travis been a female. Instead, he was a constant reminder of yet another disappointment in Helen’s life that she cursed God for.

“Why me, Lord!” were three words I should have carved on her gravestone as an epitaph if she goes before me. She had screamed them practically every day for since we’d been married: for every job I’d lost, every argument we’d had, and every bill we had to ask her father to cover. Having her only child announce that he was gay, and on the same day he told us he was moving out to be with his boyfriend in the city, topped the list. It became just another frustration she would have swept under the rug when company came over. But company never came so the things that caused her stress lay out in the open like yesterday’s newspaper or the pile of junk mail gathering on the dining room table which neither of us ever threw out.

She was a tough old gal. She married me right before Vietnam purely out of necessity for the both of us. I could draw a bigger check. She’d have good benefits and not have to work. It got her Bible-thumping parents off her back. Stupid me had a vasectomy long before the war, and even before I’d met Helen. I never told her. A reversal was imaginary back then. Everything was fine until her thirtieth birthday when she told me she wanted a baby.

I bought the ejaculate of some kid in a trashy public toilet. I’d started going there several years after we married, not attracted to Helen and unsatisfied by our almost non-existent love making. Back then, instead of hot pickles and beef jerky at Mr. Greer’s grocery, I bought boy favors from street hustlers in the park. I rushed home and pushed the sticky substance between her legs with my fingers that night and prayed. Helen was accustomed to me crying when I orgasmed, so tears shed that night were no different. I cried again a month later when she told me our prayers had been answered.

“What about AIDS?” Helen screamed the night Justin sat us down and said he had something he needed to tell us.

AIDS. Something that had never crossed my mind all those nights I’d made trips to the park, slumped between the legs of some punk kid in the back seat of my car. If I had contracted some disease by going there, it would remain a secret like everything else had in my life.

“Why me, Lord?” Helen bawled.

For the first time, Justin looked at me for an answer. Like always, I didn’t have one.

I wanted to somehow blame myself for some homosexual attribute Justin had inherited from his father’s genes, but then I remembered he wasn’t of my own flesh and blood. I still blamed myself. It was God’s punishment from where the seed had come from, and what I’d done to get it. If so, God continued to scold us by what Justin had inherited from his mother.

The gene for cancer.

Justin had begun suffering with migraines about five years after meeting Travis. Once Travis learned of Helen’s battle with cancer, he urged Justin to go see a doctor. X-rays revealed a pebble-sized tumor near the back of his head. It was easily removed. I drove Helen to the Memphis hospital to visit Justin in recovery. He had made the nurses shave his head completely bald instead of just a patch on the back where the surgery would take place. We joked about how much he looked like me. He laughed, but on the inside I knew he resented that joke. We stayed three days in Memphis at the motel directly across the street from the hospital. Travis had offered to put us up, but Justin said the apartment wasn’t big enough for three.

Doctors were confident the tumor was not cancerous, but there was no guarantee of remission. Brain cancer returned four years later, and took our son the following summer. Justin was too young to have made any prior plans for his death, and the cancer took him so quickly. He refused to think of making arrangements. He had high hopes he’d make it through.

We all did.

Travis told us that Justin had once expressed interest in being cremated. With no legal document holding us to that, Helen demanded that her son have a “proper burial.” I don’t know why I asked Travis to come along to help pick out a coffin. Helen had already changed the burial clothes he’d picked out for Justin. She put him in a suit. Justin wore a tie to work, but I don’t remember ever seeing him in a suit since the day he graduated high school.

Travis had brought a polo and jeans, Justin’s signature choice of attire. Travis also picked out a mahogany rosewood casket. It was way out of our budget, but he offered to pay half. Helen refused. She wanted a cheaper model with sky blue inlays and shiny handles. I sweated bullets when I wrote the check. Travis pulled me aside later when we’d taken Helen home. He asked if I could take him to a bank.

“Which one?” I asked.

“Any bank. How about yours? Where do you bank?”

“Citizens National.”

“Take me there,” he said.

I waited behind him in line for a teller. I was going to sit down but he asked me to go through the line with him. He’d already filled out his check and deposit slip in the car. When we reached the teller, he pulled me in front of him and handed me the check. It was made out to me.

“Deposit it,” he demanded.

“I can’t do that, Travis,” I said looking at him with shock when I saw the amount. It was enough to cover the entire check I’d written at the funeral home.

“You will. You knew that check would bounce, but you wrote it anyway even after I offered to help. Now, Helen isn’t here and can’t stop me. I knew you’d either rip it up or spend it frivolously. That’s why we are both standing here.”

“Is there a problem?” the teller asked with concern.

“I don’t have my checks with me. I don’t know my account number,” I said throwing out excuses.

“I’m sure this nice teller can look it up for you. Can we have a blank deposit slip please?” Justin said.

After making the deposit, we sat in the car in front of the bank and said nothing. I just sat behind the wheel feeling violated. Helen never touched the accounts, but I was still afraid she’d find out.

“That was more than enough, Travis.”

“The rest is to cover his headstone. Take Helen to Stuart’s Monuments when all of this is over.”

“Are you mad about the clothes? The casket?”

“No…” he said with a long sigh. He’d been staring at the floorboard. He lifted his head and looked out across the old downtown court square. There was magic in his eyes as if he was reliving a hundred sunsets. “Those things aren’t the Justin I know. It’s your Justin, or at least the Justin you want to remember.”

The Justin I wanted to remember had never been born. He died in my late teenage years just before the war, with a doctor’s incision and the snip of my vasa deferentia. The unspoken words lingered at the back of my throat. They dried my mouth like cotton. I stopped at Greer’s on the way home for a root beer to wash them back down. I had never told anyone. I certainly couldn’t tell Travis now, although it might explain a lot or it might not explain anything at all.

Rather than make things more complicated, I buried those secrets with my son. I’m not your son, Justin called out in my head from beyond the grave. He’d haunt me. He’d died and gone to heaven and some angel had whispered in his ear the truth about what I’d done. He’d come back to haunt me. I just knew he’d cut the brakes on my car on my way home from work or punch me in the chest until I had a heart attack. I could never be so fortunate. Having to walk this earth without him on it was my punishment. No matter how distant he became when he was living, he was still the hope that held the Black family together.

Helen left all of Justin’s pictures and trophies on the wall, an everyday reminder of better days. We crumbled, and Justin hung there on the wall to bear witness to every minute of it. His toothy first and second grade smiles were now like the gnashing of teeth out of anger. In a fit of rage after a fistful of pills and a bottle of bourbon, Helen had more than once smashed the pictures from the wall. She’d lay on the floor in a smatter of glass with her bleeding fists and cry out.

“Why me, Lord!”

God wasn’t listening.

I’d stopped going to church shortly after Justin passed. About a year later, I started back. It was just another way to escape the confines of the house. The congregation rarely spoke to me. I might as well have been a demon sitting on the back pew.

I was.

The preacher still shook my hand every morning at the end of the sermon when we all filed out. I always waited until everyone had passed by. I’d gained so much weight that maneuvering myself out from between the narrow pews could be quite embarrassing.

Lorraine had stopped to say hi once. She was the one smiling face I had left, always greeting me cordially and saying it was nice to see me. I had not seen Travis since Justin’s funeral. I always asked Lorraine about him.

“He’s fine. Travis is fine.” That’s all she’d say. That’s all she needed to.

A lady coughed into her hand outside as she pumped gas. The quick white smoke of her car exhaust blew by the window, lost against the piles of snow. I could hear the rotary clicks of the numbers changing on the old gas pump. She stepped back to the driver’s seat and sat down with the car door open. She put black mittens on and then fidgeted with a baby in a car seat in the back. I pulled the greasy napkin bib from my shirt and crumpled it in my hand as I watched her through the window. She looked very familiar. I’d seen her around town carrying a black man’s baby.

The pump clicked off when the tank was full. The lady crawled back out of the car to put the nozzle back. There was a snap of electricity when she touched the nozzle. A whoosh of orange flame licked at her. She screamed, breaking me from my perverted trance. The baby in the back seat shuddered awake and joined in.

“Mr. Greer! Mr. Greer!” I yelled.

Her immediate reaction was to get back in the car, either to drive away or to get the baby out. Some defense mechanism or rush of adrenaline stopped her from doing that. She took off the mittens and threw them in the car. Trying to avoid the flames, she managed to pull the nozzle out of the tank. She tossed it onto the ground. Droplets of gasoline continued to feed the rising flame. Luckily, there were no flames coming out of the gas tank on the car.

She kicked at the flames, and eventually got a foot under the hose. With her leg, she scooted the nozzle into the pile of snow the plows had pushed up next to the pump when clearing the lot. The flame went out. Mr. Greer had just made it out the door and down the steps. The lady leaned against the car in tears. He patted her arm. I couldn’t hear what he was saying to her. She took his arm and he helped her inside.

“I’m okay. I just need a gallon of milk,” I heard her say over the cowbell clanging on the door as they came inside.

She looked at me with strange eyes, probably wondering why I had not come to her aid. I bit my lip and looked back out the window to avoid her glance. She’d left the screaming baby in the car. I tried to be like some chameleonic animal blending into its surroundings, but felt more like a fat helpless pig at some county fair trough with people gawking over its size.

“Thank you, Mr. Greer. I’m so sorry,” she said paying for the gas and the milk.

“As long as you are okay, Clare, that’s all that matters. You be careful out there,” Mr. Greer said.

He followed her back outside to the car. He tapped on the back window and played peek-a-boo with the crying baby. The lady waved good-bye and drove away. Mr. Greer shook the snow from the nozzle and examined it. He put the nozzle back in the cradle and waddled back inside.

“Them White kids sho is trouble,” he said, shaking his head.

“Who was that?” I asked with a dumb look on my face over the whole thing that had just happened.

“Clare White, Lorraine’s youngest girl. You know she got a mixed baby? Her brother was just in here. He’s a queer.”

Mr. Greer didn’t give me a chance to respond. He disappeared into the back whistling to the song on the radio. I had nothing to say about her anyway. I had recognized her from Justin’s funeral, but didn’t know she was Travis’s sister. I looked back out the window and played the sudden events over in my head again, impressed at how quickly Clare had responded. I felt like an idiot just sitting here, too tired and bloated to aid someone in trouble.

She had a child in the car to think about. Her response was instant, while I just sat here with my gut pressed against the table. She was headed to Lorraine’s now and would relive the events out loud to her loved ones. Clare would say something about how her life had flashed in front of her eyes. She reacted on impulse because all she could think about was her kid.

All I ever thought about was Justin. But my life was a slow flash, and I never reacted to it at all.

Lorraine

Like every morning, I was awake by dawn. I preferred the winter months when it would still be dark outside. The earth was quiet and asleep. I felt like I had it all to myself. The old habit of tip toeing through the house, from back when I still had kids upstairs sleeping, had never gone away.

The coffee was on a timer, and if the smell of it brewing didn’t wake me first then my internal clock never failed. I don’t remember the last time I’d set the alarm clock on the nightstand. I didn’t even keep a clock there anymore. It’d been in the dresser since Frank passed. When you are the last one left in a big empty house, with no kids to attend to or lunches to make, a clock timed schedule is pretty useless. I got up with the sun, and sometimes went to bed “with the chickens” as my Granny had liked to say. And as long as my eyes opened on tomorrow, I’d get up and do it all over again.

I stretched my way out of bed and threw on my slippers and heavy housecoat. After the first cup of coffee, I picked the paper up from the front step. The obituaries were always read first. I had constantly skipped that section before I lost Frank. Now, it was as if I was waiting to find my name printed there, and I guess that would be the day I’d stop reading them again. After reading the paper, I load a pail with birdseed and go out into the backyard to fill up my three birdfeeders.

I kept a large plastic container just inside the back door filled with seed. Four bags from the dollar store filled it up. I attempted to keep it outside the back door once, but a raccoon discovered it one night and helped himself to it. I assumed it was a raccoon, and one with a sense of humor. He spilled the seeds all over the deck, ate most of it, pooped by the steps, and then carried the container off into the yard like a toy. A flock of sparrows had frightened me when I opened the back door the next morning. They had been devouring the leftover

s.

Cardinals and finches anxiously watch me from the low limbs and the fence posts, accustomed to seeing me put food out for them but still keeping safely out of sight. The two larger feeders were pretty commercial looking, and could hold a whole bag of seed. I never filled them up that much because the squirrels would come around and chase the birds away.

The third feeder was one the boys had made for me from a craft kit for Easter or Mother’s Day many years ago. It resembled a miniature barn the boys chose to paint red, white, and blue. It always made me laugh because, unbeknownst to them, three of the five children had been conceived in an old barn Frank and I used to stroll out to on the edge of the property. The barn had since been torn down when I sold several acres after Frank passed, but a coat of shellac each spring helped preserve my little barn birdfeeder.

A few weeks ago when I went to fill the barn-shaped feeder with seed, I found a small yellow oriole lying on the ground beneath it. It frightened me at first and I took a step back, expecting it to quickly fly away. When it didn’t, I knelt by it to get a closer look. It had yet to snow so the bird was not wet. Its gold colored feathers were soft and dry. Its eyes were closed as if it was sleeping.

It broke my heart because the orioles only visit this area during the winter. I see mostly sparrows and robins during the warmer months. I wanted to blame the cat, Marcus, but he was so old he rarely chased birds these days. Back when he did, he’d leave them at the backdoor for me to find and they’d look all wet and matted from where he chewed on them.

I filled the last feeder with seed and then picked up the small fragile bird and put him in the empty pail. After I showered and dressed, I retrieved a garden shovel from the garage and dug a small grave next to the koi pond. Marcus sat on a rock next to the pond and lazily eyed me, proud as if he had killed the oriole or as if I should give it to him now. With it already being dead he’d have no interest in it at all, and besides, the little bird deserved a proper burial.

“Don’t you go digging him up either,” I said to the cat. I dipped my hand in the pond water and flicked it at him. He gave a hiss and ran under the porch. The fish flopped, wanting to be fed.

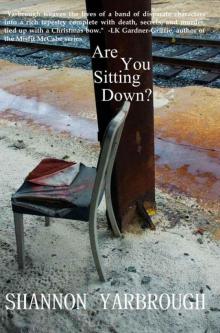

Are You Sitting Down?

Are You Sitting Down?